Last month Duncan posted the last entry for the Gastonomer's Bookshelf. The Bookshelf is now an archive of the reviews written since 2008.

As a sometime contributor I sympathised very much with Duncan's aim to give recipe books, and books about food in general, the attention they deserve and 'to give lovers of culinary books access to thoughtful and honest reviews'. In the end it just proved too difficult maintaining a site like this alongside other work commitments. But another stumbling block, even more more difficult to overcome than the need to find more hours in the day, was the difficulty of convincing people to 'review a book on the subject they love'.

I felt a pang of guilt when I read this because I have to admit to finding reviewing recipe books in particular a far more difficult task than I had imagined. My problems arose in part because of the difficulty of establishing suitable criteria and trying to maintain an objective voice. It became more and more obvious to me as I tried to justify my own reactions to certain books and to certain authors that my responses were very subjective and liable to change. For example I have always spoken highly of Nigel Slater and I have several of his books but over time I have modified my enthusiasm. So whilst I still enjoy reading what he has to say I can well understand that others may find it all a bit overblown. I wasn't very impressed with the Alain Ducasse volume I reviewed but several of my friends thought it was both very attractively presented and very useful - who am I to contradict.

But more than anything I started to question the relationship of the cook and the recipe. Why do we need more recipe books? Why when there are so many recipes available on the Internet (and almost everyone I speak to admits to looking up recipes and cooking with their iPad sitting up on the kitchen bench) why is there such an endless stream of new books?

Of course I don't have the answer to these questions but what I would like to share are some notes I took at a conference I attended earlier this year. One of the speakers was Jonathan Milder a research librarian who works for the Food Network in America and he had some interesting points to make about recipe books.

For example, most recipe books don't cite references or have bibliographies or footnotes (with of course some very notable exceptions - Stephanie Alexander, Claudia Roden come immediately to mind) so where does the information they contain come from? Few authors acknowledge the work of others, there is a fundamental ambivalence to the whole question of authorship and plagiarism and unsubstantiated claims (such as 'authentic', 'traditional' and the dreaded 'foolproof') are commonplace. Milder argued that the absence of critical discourse on cookbooks was the result of a lack of any secondary materials which would allow for assessment and criticism.

Much of what he had to say he admitted was inspired by John Thorne's introduction to his book Simple Cooking. John Thorne may not be as well known in Australia as perhaps he should be but he is a thoughtful writer and worth seeking out if you are not already familiar with his books.

In Simple Cooking he explains that his 'goal as a cook has always been not so much to attain some specific sense of mystery as to be able to just go into the kitchen, take up what I find there, and make a meal of it' but of course 'an impromptu, impulsive, and ever-adaptive cooking style is not one that the cookbook ...is by nature equipped to explain'.

Paradoxically cookbooks are not good at teaching how to cook. Thorne and Milder argue that the cooking takes place before the recipe, the cookbook cannot step back in time to that moment before the recipe so the book can only offer an act of recreation. To quote Thorne again

'Whether you follow the directions exactly or vary them to your taste, you still can't step back behind them into the sensibility that existed before it did - to that moment in the kitchen when the cook really did not know what she was going to do with all that stuff before her on the table'.

Cookbooks then just recirculate the already known, each new publication is just the latest articulation; in essence all the recipes are already written, each new version is only an adaptation. All recipes are a product of a people, place and time and the cookbook is essentially an archive of knowledge sourced from non-verbal practise.

Thorne finds it strange that there are hardly any cookbooks which encourage the sharing of 'the muddle and the mistakes and wrong turns - and to consult other cookbooks besides their own - in order to make the experience of cooking a real one. For it is exactly those hesitations, confusions, moments of panic - and then the growing sense of confidence - that shapes the experience of the real cook. The rest is only recipes ... What they offer as experience is very limiting.'

However this does not mean that recipe books don't have an important and necessary place in our cooking lives.What Thorne advocates, and practises, is that cooks should do their own research, read about ingredients and recipes, use their recipe books as resources and interrogate them. What do different authors have to say? What historical details and personal anecdotes do they have to offer?Where do they agree, how do they differ? From this information the cook takes what suits them, - what appeals to your taste and your style of cooking, what fits in with your means and the resources (both equipment and raw materials) available to you. He likens this to a conversation - bringing all these cooks together in your kitchen for a lively debate.

'Juxtaposing all these good cooks provides us with an experience far more valuable than any one of them can offer, because we are suddenly liberated from this nonsensical notion of a seamless cookery. We experience that art as it is and should be: opinionated, argumentative, contradictory, with each cook making the exact same "traditional" dish in his or her own particular way, all the while swearing it is the only conceivable one.'

John Thorne's recipes are the result of his own conversations with different cookbooks.

So perhaps this is why we need another cookbook, why we cut out recipes from magazines and newspapers and why we search the Internet, to add another voice to the conversation. My own kitchen scrap book has for example several pages devoted to variations on baked ricotta, four or five different recipes for versions of eggplant gratin, five or six recipes for variations on lemon syrup cake all with annotations and references to similar recipes in my cookbook collection. What I actually cook is my own creation,

Felicity Cloake writes a column in The Guardian where she does some of the interrogating for you and thereby adds more voices to the discussion - her article on Lemon Drizzle Cake is here.

Thanks to Wikipedia you can find out more about John Thorne here.

Simple Cooking, John Thorne,Viking Penguin, New York, 1987.

Thursday, June 20, 2013

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Alice (and Gertrude) Again

The trouble with research is that you never know when you are finished. People, places and things that you are interested in keep coming back to haunt you.

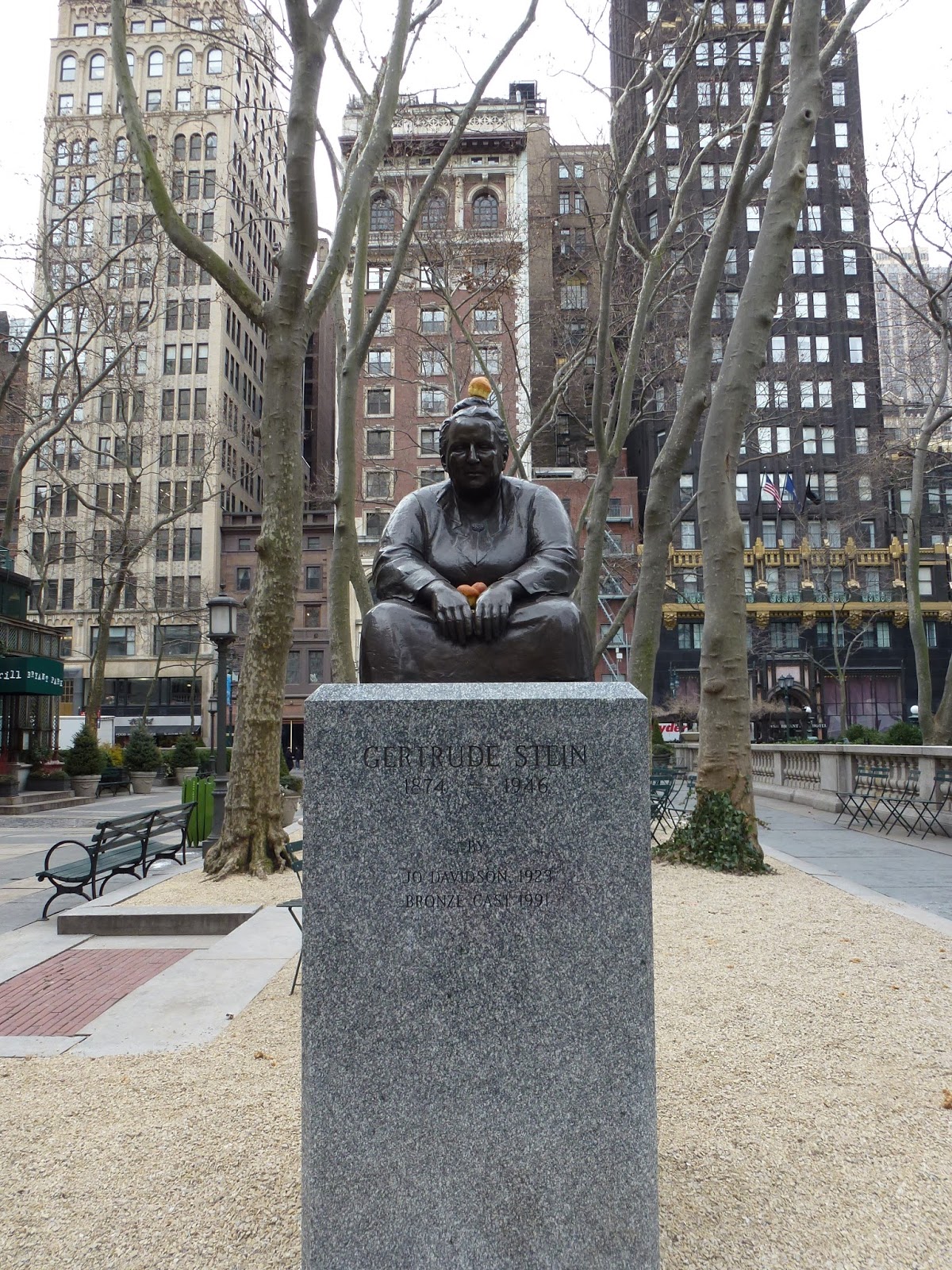

This photograph of the Gertrude Stein statue in Bryant Park, New York was taken on 7 February. Either someone knows how much she liked her little cakes or they are a gift to celebrate her birthday (on 3 February).

For more information about the statue see the Bryant Park Blog here. Bryant Park itself has an interesting history which you can read about here. I came across Gertrude (well to be truthful I was looking for her) en route to the New York City Library to see the Lunch Hour NYC exhibition (which I have mentioned before and you can read about here) but not before I also encountered Carl Van Vechten's name carved into the sandstone in the library foyer.

So can Alice be far behind? Well since I last wrote about her cookbook I have encountered more information about her too. Deanna Sidney at Lost Past Remembered here introduced me to Naomi Barry's essay in Remembrance of Things Paris: Sixty Years of Writing from Gourmet. Then reading Laura Shapiro's Something from the Oven. Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America I discovered a whole chapter on Poppy Cannon who collaborated with Alice on Aromas and Flavours of Past and Present. (which I wrote about here). Poppy herself was a wonderful character and I thoroughly recommend Shapiro's thoughtful account of her life and her legacy.

Another recent read was John Thorne's Simple Cooking which includes his review of The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book written on the occasion of the publishing of a new edition by Harper & Row in 1984. In his usual thoughtful way he begins with the problem of the aura which seems to surround everything to do with Stein and Toklas and the warning that unless you approach The A.B.T.C.B. with more than 'a few scattered impressions' about Gertrude and Alice 'you may well begin reading with puzzlement and soon sink into total disgruntlement. Because, while it would be wrong to say that this is a terribly overrated cookbook, it is very much a wrongly reviewed one.' Of the recipes he says 'they do not contrary to the reviews, make you want to rush into the kitchen and try them out' because although a cook book the pleasure lies elsewhere,

' to enjoy this book you must find your pleasure in the company of Alice B. Toklas - in a woman who knew exactly who she was. It is this that gives the book its measure of wild charm and also draws its limits, for she was a person of intense domesticity who, having established her realm, felt totally independent within it.

While the gaze she directs at the famous people who grace their table is alert, curious, even sensitive, it is also finally enigmatic, for they have no real impact on her perfect sense of self.'

And of Alice's relationship with Gertrude he says

'There is never one false note in the impeccable ordinariness with which she surrounds that liaison to ever suggest she was ever surprised, frightened, or intoxicated by what happened to her, by the sui generis nature of her life.'

John Thorne, Simple Cooking, Viking, New York, 1986.

Laura Shapiro, Something from the Oven. Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America, Penguin Books, New York, 2004.

ed. Ruth Reichl, Remembrance of Things Paris: Sixty Years of Writing from Gourmet, Random House, 2004

Tuesday, January 1, 2013

Afternoon tea with Mrs Lance Rawson

Image from State Library of NSW

In The Antipodean

Cookery Book and Kitchen Companion (2nd

ed., 1897) Mrs Rawson suggests serving 'rolled bread and butter

sandwiches made of ham paste, potted ham, tongue or chicken' for

afternoon tea. She stipulates that 'the crusts of the bread should be

cut off, and the sandwiches cut into three-corner shapes or fingers'.

She also notes that salads 'are allowable nowadays' and that 'cakes

for the purpose should be very small'. Moreover she gives specific

instructions as to the serving of afternoon tea

'For

a fashionable afternoon tea the table should be set in the rear of

the drawing-room or, if there are two rooms, in the smaller of them.

Coloured cloths are usually used, and the table can be decorated with

baskets of flowers and fruit. Do not set the plates, etc., round, but

let them be placed in piles of threes and fours here and there, with

knives, forks and spoons where they can be quickly found when

required. A few table-napkins beside them (the smaller the napkins

the better.)'

And of course 'the tea equipage should be on a separate table'.

And of course 'the tea equipage should be on a separate table'.

What

then are we to make of Mrs. Lance Rawson? She sounds for all the

world like a society hostess, very right and proper; and whilst her

tone is suggestive of someone who knows how things should be done it

gives little clue as to how much she knows about the actual doing. In the preface to her

book however she addresses her 'sister housewives' and claims her

book has been 'adapted and written expressly to meet the wants and

circumstances of those living in the far Bush, as well as those who

dwell within reach of the amenities of civilised existence'. And as

it happens Mrs Rawson knew a good deal about the wants and

circumstances of women living far from the amenities of civilised

existence.

In fact Wilhelmina (Mina) Frances Rawson was an extraordinary woman. She was born in Sydney in 1851, her father James Cahill (a solicitor, born in Ireland), her mother Elizabeth (nee Richardson, born in England). In 1857 James Cahill died and her mother remarried in 1863. Mina's step-father was a Scotsman, Dr James John Cadell, who had a medical practise in Raymond Terrace. Mina and her mother moved to Cadell's property near Tamworth where they joined his eleven children by his first wife. As Mina describes it

'When I was barely

twelve years of age, my mother took it into her head to marry a man

with eleven children. I, being an only and much adored child up to

that time, found her ideas of pioneering more tragical than

comforting, and as she added four more to the family it is hardly to

be wondered that I am somewhat resourceful.' (Queenslander 10

April 1920)

She became a great

believer in self reliance adhering to her step father's motto “When

you can't do it yourself ask for help, never before!” (Queenslander

12 June 1920)However 'pioneering' life might have been with the Cadells there was much more in store for Mina. Not yet quite twenty one she married Lancelot Bernard Rawson on 26 June 1872. Lance was probably thought to be a good catch. He was the youngest son of Charles Stansfield Rawson who had been a member of the East India Company and whose ancestral home was Wasdale Hall in the Lake District. It is unclear when Lance came to Australia but around 1867 his two older brothers Charles Collinson Rawson and Edmund Stansfield Rawson, had taken up a property on the Pioneer River near Mackay in Queensland and it was The Hollow that Lance and Mina made their home after their marriage.

The Hollow, 1874

(John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

Mackay

is described as 'an aristocratic corner of Queensland' at the time.

The climate was 'congenial' and the Pioneer River provided the

settlers there with good transport and shipping connections. At The

Hollow Mina joined Winifred and Decima the wives of Lance's brothers

who were themselves sisters, the daughters of an English clergyman

whom Charles and Edmund had travelled back to England to marry. How

Mina fitted in to this arrangement we do not know but life at The

Hollow may well have been more sedate than she had been used to. The

house was large with a fourteen foot wide verandah all the way around

reportedly covered with masses of every sort of creeper. The garden

was lush boasting poinciana trees, custard apples,lemons, limes,

guavas, grapes, mangoes and oranges, with a fernery off one side of

the verandah. The photographs suggest life was comfortable and

civilised.

Drawing room at The Hollow

(photograph by Edmund Rawson ca. 1875, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

Verandah at The Hollow ca. 1875

(photograph by Edmund Rawson, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

The Rawson sister strolling along the garden path at The Hollow in the 1870s

(photograph by Edmund Rawson, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

However

in 1877 Lance decided to branch out on his own and take up a

partnership in a sugar plantation, Kircubbin, near Maryborough. This

was the first of his not so bright ideas. The plantation was not a

success and in 1878 Mina published her first recipe book The

Queensland Cookery and Poultry Book

as a way of bringing in some income. By 1880 the plantation was

bankrupt and the Rawsons moved on to Boonooroo in the Wide Bay

region, where they were the first European settlers. Their plan was

to set up a fishery but this was another disaster.

As

Mina describes it Wide Bay was 25 miles by road from Maryborough but

in 1881 the only road was a cattle track which was impassable so the

only means of transport to Maryborough was the Brisbane steamer which

passed once a week, or their own boat, a trip of 80 miles by water.

Looking at the map today it is easy to imagine how isolated they

were. What's more Mina arrived there in March 1880 with three young

children and gave birth to her fourth child that May.

Mina

wrote up her memories of her time at Boonooroo in a series of

articles which were published in The Queenslander between

December 1919 and July 1920. She describes a hard and lonely life –

they made everything from soap, salt, candles and bacon made from

dugong to beds and mattresses and hammocks which they sold to bring

in some money. She fashioned her own furniture, entertained the odd

visitor, had some hair raising encounters with the local aborigines,

grew what vegetables she could, experimented with cooking bandicoot,

flying fox, ibis (fresh meat only came every 12 weeks) and one way or

another learnt to make the best of her circumstances. In her spare

time she wrote fairy stories which were published in one of the local

papers.

They

were not without help from friends (who contributed a number of

gadgets including sewing machines, washing machines, an American

stove, a mincing machine, a churn and not least a patent nutmeg

grater) and they were at least in contact with Lance's family who

sent them boxes occasionally but life must have been pretty grim.

Most of her female visitors fled quite unable to tolerate the

conditions and Lance was often away from home. Although she was

obviously quite capable of packing up her children and taking herself

off on the steamer to either Maryborough or Brisbane Mina stuck it

out but nonetheless she hated Lance being away. She claims she came

to understand that for her husband 'it was an impossibility for him

to stay away from the companionship of other men'.

This

is the same Mina Rawson who writes in The Antipodean Cookery Book

and Kitchen Companion,

'Man

must be cooked for. He'll do without shirt buttons, and he'll do

without his slippers, but he will not do without his dinner, nor is

he inclined to accept excuses as regards under- or over-done meals

after the first week or so of the honeymoon'.

She

goes on to warn those contemplating marriage that 'only by feeding

him well will you succeed in gaining your husband's respect and

keeping his affection'. It

would seem however that Mr Rawson had more to admire in his wife than

merely her cooking skills.I could find no photographs of either Mina or Lance. I imagine that Lance was probably rather dashing, a bit of a romantic hero, handsome and charming and able to sweep Mina along with his confidence in his plans. She does let on that he had a bit of a reputation for pranks and 'lighthearted frolics' and that her mother thought 'he must be a great trial to his nice quiet brother'. She certainly has nothing to say against him. Writing in 1920 of her time at Boonooroo she says

'I

began to feel that I could not go on living at Boonooroo. But

unhappily our circumstance would not permit of our leaving, it being

the only home we had, and as a matter of fact I was the only one

earning...When I look back at that time I could almost cry at our

childish want of practical knowledge. If we had not been young our

hearts would have been broken with the repeated disappointments of

the place. The only reason we remained was because we were almost

self-supporting, and I was able to earn enough to keep us in the

necessities we did not produce. It was simply our sense of humour

which kept us from dying too.'

Just how long they spent at Boonooroo and how their situation was resolved is unclear but Lance was eventually appointed as a Crown Lands Ranger and sometime around 1886 they moved to 'Rocklands' in Rockhampton. It was here that Mina published her other recipe books, The Australian Enquiry Book in 1894 and The Antipodean Cookery Book and Kitchen Companion in 1895, and became a swimming instructor, reputedly the first swimming teacher in central Queensland.

Lance

died in 1899. He was 56 and both of his brothers had returned to

England by then, Charles in 1886 and Edmund in 1894. Mina took on the

role of social editor of the Rockhampton People's Newspaper for

the years 1901-02. In 1903 her circumstances took another turn when

she made her way to London to marry Francis Richard Ravenhill.

Apparently Ravenhill had been Lance's business partner in the

Boonooroo venture (although I couldn't find a reference to him in her

newspaper articles) but, if his gift to the bride of of various bits

of pearl, emerald and diamond jewellery are anything to go by, he

hadn't suffered any great financial hardship as a result.. Mina wore

a wedding gown of fawn silk voile, with a toque of brown chiffon and

deep crimson roses and carried a bouquet of red rosebuds and lilies

of the valley. She had come a long way from the lonely nights writing

fairy stories in the bush. And the guests showered them with all

sorts of fancy silver gifts, including a silver crumb scoop which was

presumably of some use to them in London.

Mina

remained in London until 1905 when the Ravenhills decided to travel

to Australia. Whether this was planned as a permanent move or not is

unclear but they travelled home with Mina's daughter Minnie who had

been visiting them. I think they returned for Minnie's wedding which

was scheduled for early 1906. In the event Francis Ravenhill died at

Galston (outside Sydney) in February 1906.

What

Mina did after that I don't know other than that her memoirs were

published in the Queenslander as noted above and she died in

Sydney in 1933.

On the one hand Mina knew all about polite society. Her brothers in law were well know and well respected gentlemen (Edmund Stansfield was briefly mayor of Mackay); one daughter, Una Belle (Muffet) married Lionel Ottley Wilkinson, nephew of Sir John Ottley*; the other, Minnie, married Ronald Swanwick from a notable Queensland legal family and at the time of her engagement (1906) it was expressly pointed out that Miss Rawson was the second cousin of Sir Harry Rawson the then Governor of NSW. On the other she certainly had her own experience of reduced means and isolation. The fact that she may have had the right sort of connections doesn't detract from the fact she had seen first hand the 'wants and circumstances of those living in the far Bush'. Her books and other writings suggest that she was not afraid of getting her hands dirty, that she was both practical and imaginative and curious enough to learn from those around her (she freely acknowledged that she had learnt all she knew of indigenous foods from the Aboriginal people she had encountered) and adapt her own ideas and standards to fit her situation.

Most historians credit Mina for her use of local ingredients, for example her recipes for stewed ibis, stewed wallaby and instructions on how to prepare pig weed and bandicoot, but I wonder whether these recipes were put to much use by her readers. In dire circumstances curried bandicoot might have to suffice or might serve as a novelty but I suspect it was her knowledge of local conditions rather than her knowledge of local ingredients which was of most use to her audience. Mrs Beeton for example would not have provided information on how to deal with banana stains or how to get rid of ant's nests. The use of whatever was to hand had more to do with ideas of practicality and frugality than any desire to foster thoughts of an Australian cuisine.

And implicit in all Mina's writing is the idea of bringing civilisation to the Bush and the important role that women had to play in this civilising process. Did Mina have her 'tea equipage' on a separate table when she entertained visitors at Wide Bay? Did she even have a separate table? Whether she did or not she obviously thought it most important that her sister housewives should know the right way to do things and should aspire to maintain their standards regardless of their circumstances.

* It was Mrs E. R. Ottley, Sir John's mother, described as an early settler of Rockhampton, who owned Rocklands Estate. Lionel and Una Belle were married at Rocklands in 1899 but I haven't been able to work out how Mina and Lance came to be living at Rocklands. The Wilkinson family were also associated with Rocklands station, Camooweal.

For more information on the Rawson family and The Hollow see here.

Details of Mina's life were gleaned from the Australian Dictionary of Biography here and from newspaper searches via the Trove web site here. To the best of my knowledge there is no other published biographical information about Mina and Lance. A search of Trove will also yield a number of photographs, paintings and drawings of the Rawson family and life at The Hollow.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)