|

Alice at rue de Fleurus with some of the 'sparkling' silver.

Man Ray, 1922. |

After I read

The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book I went looking for as much as I could find about Alice and Gertrude and food (without having to resort to reading any of Gertrude's works which I think might be a bit beyond me). I wanted to fill in some of the gaps in Alice's story and try to understand more about the role food and cooking played in her life and in her relationship with Gertrude. I don't know that I am necessarily any the wiser but herewith, in no apparent order, are some of the bits and pieces which I found interesting.

Before Alice came to Paris she had led what Gertrude called in

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (hereafter AABT) 'the gently bred existence of [her]class and kind'. She had grown up in a household where there were cooks and nurses. With her mother's death she had taken on the management of that household – such as the menu planning and budgeting – rather than the labour of actually preparing meals. In the

The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book (hereafter ABTC) she tells us that before she came to Paris she 'was interested in food but not in doing any cooking', she read cook books, she collected recipes, but most importantly she enjoyed eating. In the preface to

Aromas and Flavours she talks of the 'rapture and surprise' she experienced on her first tasting 'a steak smothered in garlic' although her adventurous palate was not considered entirely appropriate, 'garlic was not admitted in my mother's kitchen, nor did she consider my enjoyment of the strong flavour of salmon, sweetbreads, brussels sprouts, all cheese, caviare, the onion family including garlic, and wine, natural or commendable in her young daughter'.

|

| Alice and Gertrude at 27 rue de Fleurus, Man Ray, 1922. |

When she first moved to 27 rue de Fleurus to live with Gertrude Stein the cook was Hélène, an 'invariably perfect cook' who 'knew all the niceties of making menus' (ABTC p. 171). Alice claims that she learned nothing about cooking from Hélène because Hélène did not think it appropriate for a lady to cook. Both Alice and Gertrude tell stories about Hélène and her understanding of the role food played in the social niceties. As Gertrude tells it

Hélène had her opinions, she did not for instance like Matisse. She said a frenchman should not stay unexpectedly to a meal particularly if he asked the servant beforehand what there was for dinner. She said foreigners had a perfect right to do these things but not a frenchman and Matisse had once done it. So when Miss Stein said to her, Monsieur Matisse is staying for dinner this evening, she would say, in that case I will not make an omelette but fry the eggs. It takes the same number of eggs and the same amount of butter but it shows less respect, and he will understand. (AABT, p.16)

But in Alice's version the lesson she learnt from Hélène was more complicated and subtle

If you wished to honour a guest you offered him an omelette soufllé with an elaborate sauce, if you were indifferent to this an omelette with mushrooms or fines herbes, but if you wished to be insulting you made fried eggs. With the meat course, a fillet of beef with Madeira sauce came first, then a leg or saddle of mutton, and last a chicken. (ABTC p. 171).

I think that if she did not already know, Alice would have quickly appreciated that food could play a significant part in her relationship with Gertrude, not just providing sustenance and a sign of affection but also as an important contribution to the gatherings of Gertrude's salon. The guests, the artists and writers, who came to rue de Fleurus in the 1920s and 30s came to see Gertrude but it was Alice who opened the door to them. The conversation may have belonged to Gertrude but the food belonged to Alice. Alice choreographed the proceedings and regulated the atmosphere of those gatherings, at least in part through what she served and how she served it. Even if their guests did not appreciate it, Alice would know that what they were eating reflected how much they were valued.

Hemingway describes Alice working on her needlepoint while he talked to Gertrude and Alice talked to his wife. Alice saw to the food and drink and at the same time 'she made one conversation and listened to two and often interrupted the one she was not making'

(A Moveable Feast)

. Bravig Imbs, who first met Gertrude in 1926, 'realised instinctively that Alice was important and required attention',

Gertrude received so many people that she could not be bothered worrying whether they would get on together, but let all classes and kinds mix pell-mell and the devil take the hindmost. All she cared about was to shake loose the people who bored or annoyed her and though she was too kindly to drop them in the middle of a sentence, she always managed to introduce them to Alice before the sentence was ended. Alice acted as both sieve and buckler; she defended Gertrude from the bores and most of the new people were strained through her before Gertrude had any prolonged contact with them. That was why after the preliminary handshaking, I found myself taking very delicious tea and munching heavenly cakes with the gypsy-like person ...She talked a blue streak.

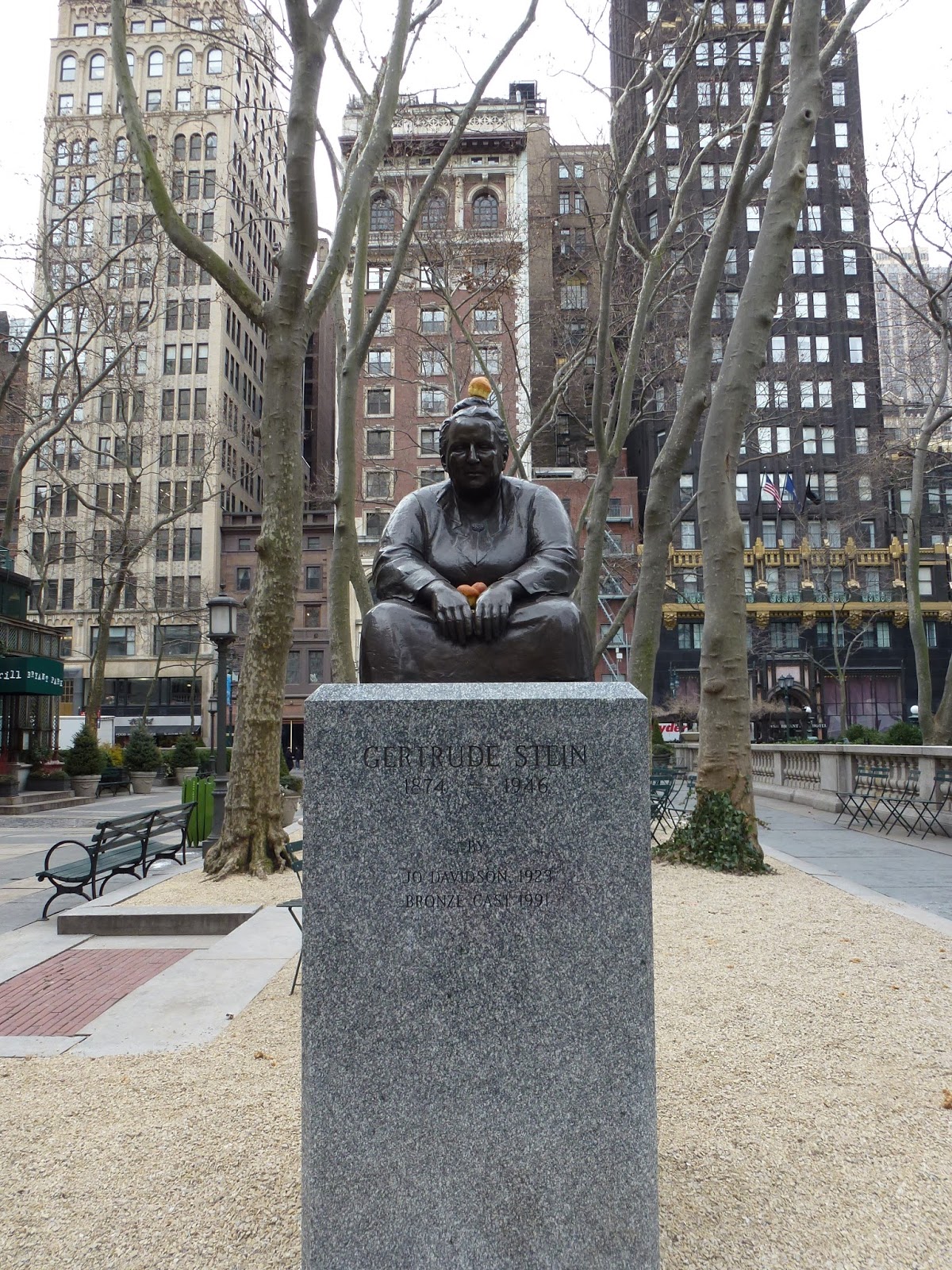

What a shame he doesn't tell us what she talked about. Sir Francis Rose, who was first introduced to the pair in the summer of 1937, describes Alice sitting behind a tray 'sparkling' with silver urns and teapots, surrounded by small tables 'covered with beautiful china, heaped with all kinds of home-made cakes, marrons glaces, crystallized cherries and violets'. Most commentators accept that Alice's role was to entertain the women guests, the wives, while Gertrude talked with the men, and to serve the tea and cookies. Rose observes that she was 'always watching the guests like a cat to see that everything was going well and that good manners, according to the Victorian standards of the house, were being observed'.

Whilst some visitors appreciated Alice's attentions others found her intimidating and difficult. Françoise Gilot describes being taken by Picasso to meet Alice and Gertrude, a scene which would be funny except for Gilot's obvious discomfort and for the fact that it paints both Alice and Gertrude as rather ungenerous to their young guest. She was ushered into the salon and 'Alice Toklas sat down on the divan beside me but as far away as possible. In the centre of our little circle were several low tables covered with plates of

petits fours, cakes, cookies, and all kinds of luxuries one didn't see at that period, right after the war.' Whilst Gertrude was cross-examining Gilot

Alice Toklas was not sitting down, but bobbing up and down, moving back and forth, going out into the dining room to get more cakes, bringing them in, and passing them around ….when ever I said anything displeasing to Alice Toklas, she would dart another plate of cakes at me and I would be forced to take one and bite into it. They were all very rich and gooey and with nothing to drink, talking was not easy. I suppose I should have said something about her cooking, but I just ate her cakes and went back to talking with Gertrude Stein, so I guess I made an enemy of Alice Toklas that day.

Did Alice and Gertrude disapprove of Gilot or were they trying to give Picasso some sort of message? In the end Gilot promised herself that she would never visit the apartment again and concluded that it was easier to do without Gertrude altogether 'than to take her in tandem with Alice B. Toklas'.

Cakes and sweet things seem to have played a large part in their lives. Apart from what was served to visitors, according to Natalie Clifford Barney, another expatriate American who had a salon in Paris, Gertrude and Alice were always on the look out for new cakes. She rather neatly concludes that Gertrude 'must be sustained on sweetmeats and timely success, this being the surest way of taking the cake and of eating it and having it too.' Alice would have learnt early on that Gertrude had a sweet tooth, and, according to Harold Acton, 'cosseted' her with creamy cakes. Alice may not have known too much about cake making when she first came to Paris, ordering them instead from the baker since Hélène's talents didn't stretch to fancy pastries either, but eventually she earned a reputation for them. Writing to Annette Rosenshine in 1951 she says

When I used to bake a cake for Gertrude I never asked is it good I always said does it look like one that came from the bakers ... well it was often that Gertrude thought that it did.(Burns ed, p. 237)

Natalie Barney recalled a summer afternoon at Bilignin when Alice served a 'fluffy confection of hers, probably a coconut layer cake which only Americans know how to make – and eat' which came with white icing edged with pink. Clare More de Morinni, chairman of the American Women's Club in Paris, was delighted to be invited to 'sample one of Miss Toklas's wonderful cakes'. But for all that they may have been important cakes are not disproportionally represented in

The Cook Book and you will search in vain to find Gertrude's favourite or the recipe for coconut layer cake. Many of the recipes are not what Alice herself cooked, they are recipes she collected, recipes for dishes she enjoyed, so whilst she doesn't necessarily tell us what she liked to prepare we do know what she liked to eat.

|

Alice and Gertrude at 5 rue Christine, 1938

Cecil Beaton |

Alice did pretty much everything for the two of them while Gertrude sat around being a genius. Gertrude has Alice say 'I am a pretty good housekeeper, and a pretty good gardener and a pretty good needlewoman and a pretty good secretary and a pretty good editor and a pretty good vet for dogs and I have to do them all at once '(AABT p. 256). What she doesn't say is that Alice was a good cook.

She first cooks for Gertrude only on Sunday evenings, when Hélène was at home with her husband, which was when 'Gertrude Stein liked from time to time to have me make american dishes' (AABT p. 122). For all that they spent most of their lives in France, returning to America only once, and both women came from families imbued with European sensibilities and culture, they both seem to have always remained Americans abroad and proud of it. So Alice prepared Gertrude 'the simple dishes I had eaten in the homes of the San Joaquin Valley in California' (ABTC p. 37) and presumably coconut layer cake, and W. G. Rogers sent them seeds of American corn each year for the Bilignin garden. In 1949, writing to Annette Rosenshine Alice comments that a Chinese restaurant she has been to in Paris was 'nice but not like in S.F. oh dear no' and in 1951 she writes to Claude Fredericks of 'a California recipe for pecan pie with rum and the pecans glazed on top that I've read for years that we might enjoy' (Burns, ed. pp. 157 and 231). Both were enormously proud of the American forces and their role in the liberation of France. Harold Acton commented, on meeting Gertrude and Alice just after their return to Paris at the end of the war, that 'Gertrude had become more aggressively American in idiom and the use of slang'. In Paris their friends were in the main expatriates of one sort or another and the common language of their conversation over Alice's cakes must have been English. It seems to me that living in Paris allowed them a freedom to be themselves which they could not have enjoyed in America, living apart from the French society which surrounded them in a way that they could not have achieved had they been merely trying to separate themselves from their social milieu. According to Gillian Tindall there were probably as many as forty thousand Americans living temporarily in Paris during the 1920s. She goes on

It is from this era that one can date the curious phenomenon, still observable on the Left Bank today, of an almost hermetically sealed anglophone world with its own cultural preoccupations, its own bookshop (Shakespeare & Co.), its own parties and dramas. It also has its own folk memory of former figures, from Gertrude Stein and Hemingway, to the more recent Allen Ginsberg and William Styron, which hardly interacts with the French inhabitants' perceptions of the Left Bank in anything but the most superficial way. The Paris 'to which all good Americans go when they die' has always been ...a different place from the one the local inhabitants know.

Is it too much of an exaggeration to suggest that, at least until they were exiled to Bilignin during the Second World War, Gertrude and Alice interacted with French culture largely through their liking for and indulgence in French cuisine?

|

Rue de Fleurus, 1922, Man Ray.

This photograph shows Alice entering the studio adjacent to their apartment, where Gertrude wrote, . |

If the idea of living the bohemian life in Paris appears romantic and exotic the reality was anything but luxurious, although Alice and Gertrude no doubt lived a more comfortable existence than many of their working class French neighbours. Until 1938 they lived at 27 rue de Fleurus, a stone building dating from the 1890s. Their two storey apartment was off a paved courtyard with a small hallway separating the kitchen from the dining room, and two bedrooms and the bathroom upstairs. Gertrude wrote in a separate studio adjacent to the apartment. In 1914 with Alice permanently established there and Gertrude's brother, Leo, gone they had a covered hallway built between the studio and the living area, they had the studio painted and the house papered and finally had the gas lamps removed and electricity installed. Electric heating wasn't introduced until 1929. There is no mention of the cooking facilities but it seems likely that Alice first cooked for Gertrude on a fuel stove. Their move to 5 rue Christine was a wrench but made easier to bear because of the inadequate conditions at rue de Fleurus, the apartment was dark and airless and 'no servant would stand the kitchen' which suggests that the kitchen facilities were primitive and antiquated. The move also resulted in the acquisition of a refrigerator and gifts of an egg whisk, a garlic crusher,a meat thermometer and a lid opener from friends (Souhami, p. 226). When Alice and Gertrude first started spending at least six months in the summer at Bilignin, where Alice cultivated her much loved vegetable garden, they had no inside plumbing. It wasn't until

The Autobiography was published and successful (1933) that they could afford to have a bathroom and lavatory installed, which presumably meant that the kitchen now had a water supply, and to replace the coal fired stove with an electric cooker (Souhami p. 195).

In

The Autobiography Gertrude claims on Alice's behalf that 'I like cooking, I am an extremely good five-minute cook'(p. 122) but Alice tells us that 'cooking is not an entirely agreeable pastime' because 'there is too much that must happen in advance of the actual cooking'. She goes on

In the earlier days...if indulgent friends on this or that Sunday evening or party occasion said that the cooking I produced wasn't bad, it neither beguiled nor flattered me into liking or wanting to do it. (ABTC p. 37)

She then says that she did not begin to cook seriously until 'it suddenly and unexpectedly became a disagreeable necessity' while they were in exile in Bilignin during the war and their life with servants had at least temporarily come to an end. (A chapter in

The Cook Book deals with some of the cooks Alice employed who worked for them in Paris and travelled with them to Bilignin for the summer.)

What should we make of this? It seems clear that Alice could cook when she wanted to or needed to but she preferred not to or at least preferred to make quick and easy five minute dishes. She came from a home in San Francisco which had boasted an "automatic" freezer for ice cream (ABTC p. 97) so she would have found the conditions in the kitchens in Paris and Bilignin very primitive and cooking would have been hard work. Alice's passion was food, she loved eating, she loved growing her own ingredients ('there is nothing that is comparable to it, as satisfying or as thrilling, as gathering the vegetables one has grown' ABTC p. 266) but cooking was just a practical necessity which took her away from the 'many more important and more amusing things' that she enjoyed (ABTC p. 37).

|

| This and the following two photographs were taken by Carl Mydans for Life Magazine. They show Gertrude and Alice and their dog Basket 'on the doorstep of their home during the US 7th Army's liberation of southern France'. These are my favourites of Alice because they show her in a less severe and mannered pose and because she and Gertrude are shown as equals, rather than Alice being relegated to the background. |

When Alice says that many first-rate women cooks have 'tired eyes and a wan smile' (ABTC p. 82) I wonder if she had herself in mind.

Alice was extremely resourceful and capable – she could knit, she produced needlepoint based on designs drawn by Picasso, she spent her summers digging and planting a glorious vegetable garden aside from all her duties as hostess, housekeeper and secretary – and she loved luxury and extravagance. We know from

The Cook Book that the food she enjoyed most involved cream and eggs, cognac and champagne,

foie gras and truffles, served with lashings of crystal and silver and lace. Not that she was incapable of appreciating simplicity, she just loved a bit of indulgence. When she was driving around France in 1917 she armed herself with the newly published 'booklets on the gastronomic points of interest' (ABTC p. 102) and it was the Guide des Gourmets which led them to Bilignin (AABT p. 228). Even in old age, alone and destitute she craved the finer things. Doda Conrad writes that it was difficult to satisfy her 'I remember tricking her by having fruit brought to her in used bags from Fauchon or Hédiard. This gave her the illusion of eating the best food Paris had to offer' (Malcolm p. 218).

For all that we know about Alice and Gertrude, from what they wrote about themselves and from what others wrote about them, Alice in particular remains elusive. As Janet Malcolm puts it 'biography and autobiography are the aggregate of what, in the former, the author happens to learn, and, in the latter, he chooses to tell'. In this case

The Autobiography tells us as much about Gertrude Stein as it does about Alice.

Whilst

The Cook Book is Alice's memoir it is somehow oddly impersonal. She tells us only just as much as she wants us to know about the personal details of her life with Gertrude and reveals almost nothing of her own thoughts or feelings. Her other memoir

What is Remembered adds little or nothing to the two earlier works. Trying to find the Alice who existed before the publication of

The Autobiography is almost impossible. Sadly all her early letters to her father (written regularly from 1907 to 1922), those she wrote to childhood friend Clare Moore de Gruchy, all her early letters to Annette Rosenshine and most of her pre-1946 letters to Louise Taylor have either never been found, were wilfully destroyed or simply lost.

What she looked like is easy enough to gauge from the photographs. Obviously no conventional beauty at best she is described by those kindly disposed to her as 'slim,dark and whimsical' (Sylvia Beach), 'enigmatic and dark' (Clare More de Morinni) and 'tiny and hunched .. with her hooked nose and light moustache' (Harold Acton) and at the other end of the spectrum as 'incredibly ugly, uglier than almost anyone I had ever met' (Otto Friedrich in Simon p. 211). Those who did not warm to Alice saw her as 'hideous...she looked like a witch' (Joan Chapman in Malcolm p. 188) 'with large, heavy-lidded eyes, a long hooked nose, and a dark, furry moustache' (Françoise Gilot).

Hemingway thought she had 'a very pleasant voice', but found her 'frightening'. In

A Moveable Feast he can't bring himself to use her name, referring to her only as Miss Stein's friend or companion. Many people who met her found her intimidating, several were a little scared of her. Mabel Dodge thought she was insidious and 'somehow dishonest' (Simon, p.81). Some responded to Alice's wit and vitality (W. G. Rogers), found her dignified, appreciated her shrewdness 'the cultivated and slightly grainy quality of her voice' and her warm, malicious laughter (Otto Friedrich) and took the time to discover her 'intelligence and culture' (Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler). Whilst there seems to be little doubt that she was jealous of her role in Gertrude's life and that she could be wilful and manipulative she still had life long friends like Annette Rosenshine who had been a neighbour in San Francisco and Louise Taylor who had been a friend since they studied music together and the letters written later in her life radiate graciousness, from them 'she emerges ...as a great lady, witty, self-deprecating, attentive, cultivated' (Malcolm, p. 210).

I still can't help but think that it's too bad neither Gertrude nor Alice nor any of the people they entertained bothered to leave us a description of Alice cooking in the kitchen at rue de Fleurus.

References

All quotations are from Linda Simon,

Gertrude Stein Remembered (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1995) unless otherwise acknowledged.

Burns, Edward (ed.).

Staying on Alone. Letters of Alice B. Toklas, Liveright, New York, 1973.

Malcolm, Janet.

Two Lives. Gertrude and Alice, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007.

Souhami, Diana.

Gertrude and Alice, Phoenix Press, London, 2000.

Simon, Linda.

The Biography of Alice B. Toklas. Doubleday, New York, 1977.

Stein, Gertrude.

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Zephyr Books, Stockholm, 1947.

Tindall, Gillian.

Footprints in Paris, Pimlico, London, 2009.

Toklas, Alice.

The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, Harper Perennial, New York, 2010 (1984 edition).

What is Remembered, Michael Joseph, London, 1963.

Aromas and Flavours of Past and Present, Michael Joseph, London, 1959.